Nerd Alert: this blog post may cause irrational desire to look at compost under a microscope.

Ever since I took Alane Weber’s compost immersion workshop last year, I have been trying out the techniques I learned to make better compost. In our test garden, we’ve been building Active Batch Thermal compost piles as well as cold compost piles (slowly adding material over time) with plenty of water and a good balance of carbon and nitrogen materials. The results look good, but we wanted to know what was really going on in there. Would this compost be suitable for brewing compost tea? Was our compost biologically active or not?

There’s only one way to find out for sure.

Sheri Powell-Wolff of Compost Teana, who helped organize Alane’s workshop, offered to take a look at our compost using her high powered microscope and computer. We took samples from 2 piles: one Active Batch pile and one cold composted pile that was not quite finished yet. We mixed each sample with water that was pre-mixed with some humic acid, then Sheri put one drop on a slide and down the rabbit hole we went.

First: the Active Batch compost, which had been sifted once and stored for future use. There we saw it. Bacterial clusters, ciliates (protozoa with cilia–nutrient cyclers of the microbial world), and even a flagellate or two. It was so exciting to see life moving through this microscopic space. Long story short: these are the characters who, by consuming one another, facilitate the uptake of nutrients in plants. They are part of the Soil Foodweb.

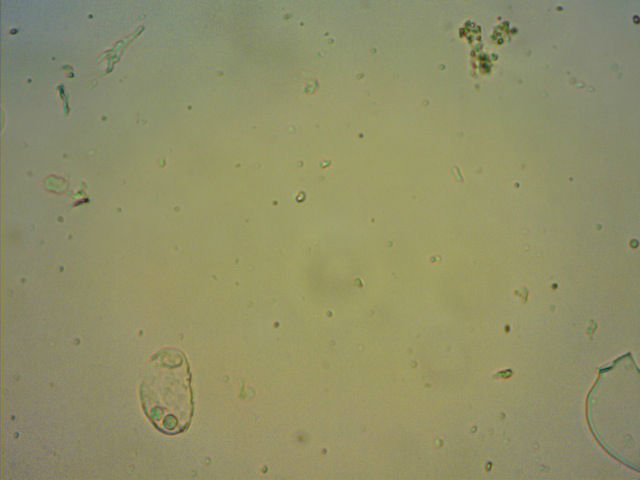

Next: the cold compost sample. Surprisingly, we saw more biological activity in this batch than in the finished compost. One reason might be that it wasn’t finished yet, and the microbes were still in the process of breaking down organic matter, or perhaps it’s because cold composting doesn’t heat up past 110 degrees, so nobody dies in the fire. Not sure which is the case, but here’s what we saw:

Those strands are fungal clusters – the good kind. The dark brown color indicates that these fungi are full of humic acid–a good quality to have. This was a very good sign that if we brewed compost tea with this batch, we’d have highly microbially active tea.

The second sample also revealed at least one bacterial-feeding nematode, which is another good critter to have in your arsenal of microbes. These nematodes help control disease and cycle nutrients. We could have watched it move around for hours.

Beneficial microbes are as important to plants as water and oxygen are to humans. The more you learn about what’s going on in your soil, the more you will garden in ways that benefit your soil (using compost and compost tea, avoiding insect sprays and chemical fertilizers, etc.).

If you live in Southern California, you can join Alane Weber’s next Compost & Sustainable Soils Workshop which will be held August 9-12, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. at the Tree People Conference Center in Beverly Hills. You’ll learn about the Soil Foodweb, how to make compost and compost tea, and how to use them both in your garden.

Good post. Yes the beneficial microorganisms in the compost are extremely important for a number of reasons – Thanks for the post.

Pingback: YouTube: Harvesting Compost | Gardenerd